- Home

- Jennifer A. Nielsen

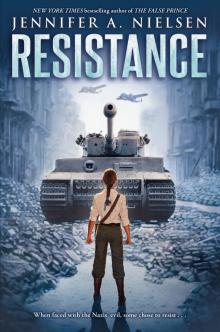

Resistance

Resistance Read online

To those who resisted,

in every way they resisted, this book is for you.

For the young Jewish couriers,

I hold you in the highest respect.

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Part One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Part Two

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Part Three

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Chapter Forty-two

Chapter Forty-three

Chapter Forty-four

Chapter Forty-five

Chapter Forty-six

Chapter Forty-seven

Chapter Forty-eight

Chapter Forty-nine

Afterword

Sneak Peek at A Night Divided

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Jennifer A. Nielsen

Copyright

Defense in the ghetto has become a fact. Armed Jewish resistance and revenge are actually happening. I have witnessed the glorious and heroic combat of the Jewish fighters.

—Excerpt from the last letter of

Mordecai Anielewicz,

April 23, 1943

October 5, 1942

Tarnow Ghetto, Southern Poland

Two minutes. That’s how long I had to get past this Nazi.

He needed time to check my papers, inquire about my business inside the ghetto. Maybe he wanted a few seconds to flirt with a pretty Polish girl. Or for her to flirt back.

But no more than two minutes. Any longer and he might realize my papers are forged. That it’s Jewish blood in my veins, no matter how Aryan I look.

“Guten Morgen.” This one greeted me with a smile and a hand on my arm. I learned early not to smuggle anything inside the sleeves of my coat. You only had to be stupid once, and the game was over.

This officer was younger than most, which I once believed would give me an advantage. I’d thought the younger ones would be more naïve, and maybe they were. But they were also ambitious, eager to prove themselves, and fully aware that capturing someone like me could earn them an early promotion.

“Guten Morgen,” I replied in German, but with a perfect Polish accent. I smiled again, like we were old friends. Like I wasn’t as willing to kill him as he was my people. “Wie geht’s?” I didn’t care how he was doing, on this morning or any other, but I asked because it kept his attention on my face rather than my bag.

Like other ghettos throughout Poland, Tarnow Ghetto had been sealed since nearly the beginning of the war, cut off from the outside world. Cut off from Jews in other ghettos. This isolation gave total power to the German invaders. Power to control, to lie, and to kill.

For the past three months, I’d worked as a courier for a resistance movement known as Akiva. My job was to break through that isolation, to warn the people, and to help them survive, if I could. But we were increasingly aware that time was running out. We’d seen people being lured onto the trains with promises of bread and jam, pacified into thinking they were being relocated to labor camps. Then they were crammed into cattle cars without water or space to move. And their destination was never to a labor camp.

They were headed for death camps, designed to kill hundreds or even thousands of people a day. I’d seen them. Been sickened by them. Had my heart shattered by them.

The Nazis called these camps their solution to the so-called “Jewish problem.”

Yes, I very much intended to be their problem.

Which required me to stay calm now. Just inside the ghetto, I saw an open square that used to be a park. Now it was a place for trading, for begging, for a population with little more to do than wander about and wonder when their end would come. Maybe some even wished for it.

As was generally the case at the gates, there was one other Nazi on duty, this time a man in an SS uniform, the more specialized military force. There were also two Polish police officers and two members of the Jewish police, whom we called the OD. They often were as brutal as the Gestapo, and no more trustworthy.

I offered the soldier my Kennkarte before he could ask, because he’d need to see the identification anyway and my two minutes were halfway up. The passport-sized bifold contained my picture and fingerprints. Everything else inside—the dates, the stamps, the personal information—was forged.

One of our leaders, Shimshon Draenger, did all the forgeries for Akiva. He was so talented I believed he could forge Hitler’s signature and fool Hitler himself with it. We sold Shimshon’s forged papers inside the ghettos as our way of funding the resistance.

“You are Helena Nowak?” the soldier asked.

I nodded, a lie that I’d told many times over the last three months, and one that I would certainly tell again. A thousand other Polish girls might have the same name, which was the plan. If all went well, he’d believe me, then in the same instant, forget me.

“Why are you coming to the Tarnow Ghetto today?” he asked in German.

I scrunched my face into a pout, a careful balance between hinting that I wished I could go on a picnic with him instead, but not enough to actually encourage him to invite me. I replied, “Shawls for the women. Winter is coming. I can make money in there.”

He frowned. “Where do you get these shawls?”

“My grandmother knits them.”

My grandmother, whom I recently smuggled into hiding with a Christian family in Krakow. She sews, cooks, and cleans for them. In exchange, they don’t have her killed. They saw it as a fair bargain, and maybe it was. If they were caught, they’d be killed too.

“Let’s see your bag,” the officer asked.

It was worn on my back, and was narrow and deep. Deliberately sewn that way. I had packed the top half of the bag tightly, making it difficult for him to dig around, if he felt the need to do so. But I hoped he wouldn’t because today, the thick shawls hid the potatoes I was smuggling in, along with some forged identification papers. For sneaking in a single potato, this Nazi could shoot me here on my feet. For the papers, my punishment would be far worse.

I turned and hummed a little tune while he looked the bag over. This was by far the most dangerous part of my mission. If I’d raised his suspicions. If he wanted to impress his commander. If he looked at me and saw the Jewish girl inside, the one who has trained herself to look these evil men in the eye and to smile and make them think I sympathize with their slaughter of my people. If he saw that, it was all over.

But I’d get in today. And tomorrow I would lie my way into another ghe

tto, and do the same every tomorrow after that until my last breath, or theirs. After three years of war in which I’d felt helpless against the overwhelming force of the German army, I was finally doing something. I was bringing my people a chance to survive.

Ghettos themselves were nothing new to the Jews. Many times throughout our history, we’d been forcibly segregated, often behind walls. Which made it harder to get people to listen now. They believed the German lie that if we cooperated, we would get through this, as we had in the past. They wanted the ghettos to be what they’d always been: a separation, and nothing more.

But it was different this time. The German plan was not to divide us from the population. It was to eliminate us from the population. To exterminate us.

The ghettos played a key role in their plans, suspending the Jews in a halfway point to everything. Half-starved, treated as much like animals as humans. Existing halfway between hope and despair.

Halfway between life and death. The one became the other in the ghettos.

And I was doing everything I could to stop it.

It began with smuggling. I’d become creative about how I brought things in: weapons baked into loaves of bread; fake identification papers sewn into the linings of my coat; or, occasionally, the smuggled object might make my bust appear larger than it really was. Whatever I was secretly carrying, I always brought information to the residents of these sealed ghettos about what was happening elsewhere, and then learned everything I could to warn the next ghetto.

But that was only the beginning. My mission today was bolder than usual, and I was nervous.

“You must leave before the ghetto curfew at seventeen hundred hours,” the Nazi told me, then with a smile added, “Come out through this gate, pretty girl, no?”

I offered him a smile of my own, one that shot bile into my throat. I couldn’t come out this gate now. Not if he was specifically watching for me.

He let me pass, and then I was in.

I wondered if he’d sensed how hard my heart was beating back there, if he’d known my palms were dampened with sweat. I’d talked my way past the soldier by making him think I was Polish. Now came the harder part: convincing my own people that I was one of them. For if they did not trust me, coming here was a waste of time.

I turned down the nearest street, hoping to get out of sight if any guards looked back. It was time to be Jewish again. I put the necklace with the Catholic crucifix in my pocket and repeated my true name under my breath: Chaya Lindner.

I was named for my grandmother, as she was named for hers. Every time I passed myself off as a Christian girl named Helena, I wondered: Was I dishonoring my name, or preserving it?

Maybe it didn’t matter. I was committed to my fate. I’d be a courier for as long as a courier was needed. I’d be a fighter if that was needed.

If a martyr was needed, I’d be that too.

But for now, this ghetto needed to see a Jewish girl. If it was difficult to pass myself off as a Pole back at the ghetto gates, it was no easier now to make the people here trust me as a Jew. I was a stranger with a Polish look, and that made me suspicious.

I was supposed to make contact with a resistance member here, but until he found me, I began distributing the potatoes. Like everything else, I passed them out as quietly as possible. I didn’t want to be recognized, or remembered. Even among my own people, there were some who might point me out to a Nazi if they thought it’d buy their family another day to live.

So whenever possible, I distributed food to children, slipping a potato into their bag or coat pocket, then quickly moving on. I sometimes looked back to see their eyes light up when they felt it with their hands, but they were always smart enough not to bring the potato out in the open, and too excited to look around for me. Usually, I didn’t look back. It wasn’t worth the risk. I moved fast, eyes down, trying not to think about who got the potato and who I’d passed over. They didn’t deserve hunger more than the child whose bag happened to be open, but such was the randomness of life. I would never be able to bring in enough food for everyone.

At my best, I could not save them all.

That thought always destroyed me. Always.

Far too soon, the supply of potatoes was gone. So what if twenty families had a potato to eat today? Couldn’t I have snuck in even one more? I lowered my eyes and clutched my bag in my hands. I couldn’t give out the shawls—no matter how cold it was about to become, I needed them for the second part of my mission. But I had to find my contact soon.

The German invaders had taken everything from me: my home, my family, even much of my faith, which had once been the center of my life.

So I had no problem taking something back from them: my dignity, my fight. My will to live.

But if I’d learned anything from this war, it’s that we can never go back.

September 1, 1939–April 22, 1941

Krakow, Poland

Over my sixteen years, I’d lived three different lives. The first was my childhood, full of peace and beauty and memories that lingered in my mind like a faint perfume, sweet but always just out of reach. My father owned a shoe repair shop, and Mama used to sing as she cooked us masterpieces of fish baked in cream sauce, or lamb dumplings, her specialty. My brother, Yitzchak, was two years younger than me, mischievous and playful. My sister, Sara, a few years younger than that, had hugs that were made of magic and she gave them freely. Our lives used to be perfect.

Used to be.

The Germans invaded Poland on my thirteenth birthday, a Blitzkrieg that came with tanks and bombers and thousands of deaths before our country surrendered that same month. Poland became occupied territory under Germany’s control and Krakow replaced Warsaw as its new capital city. With our country’s waving of the white flag, thus began my second life: enduring the occupation.

New laws and regulations were immediately instituted, most of them targeting my people. German tanks rolled through the streets, particularly the Jewish quarters, issuing orders through bullhorns that all Jews must register with the new government.

“Don’t do it,” I warned my parents. “Don’t give them our names.”

“You heard them.” Papa always preferred to be cautious. “The penalty for refusing to register is death.”

Maybe it was. But I had a terrible feeling that the penalty for registration was also death.

Within weeks, the invaders barged through our front door with orders to search all Jewish homes. They combed meticulously through our drawers and cupboards and wardrobes, even cut open the mattress on Sara’s bed to search inside it. Officially, they took our jewelry and foreign currencies, which we were forbidden to keep. Unofficially, they took anything they wanted. My mother’s fur coat that had been an anniversary gift from Papa. A violin that Yitzchak had saved up for months to buy. They tossed our prayer books into the square and burned them, simply because they could. At the time, I’d been relieved, thinking that they had taken nothing from me.

But they would. Very soon, they would take everything.

Like a hungry fire, their destruction continued throughout the city. Our national monuments were looted, synagogues were burned, and the bronze statue of our national poet, Adam Mickiewicz, was taken for scrap metal.

One month later, forced labor began. Jews were made to dig ditches, pave roads, and drain swamps. If they were paid at all, it was with a mouthful of bread and little more.

Papa and I were on the streets one day when I happened to look down at a man cleaning out sewage from a broken pipe.

“That’s our rabbi!” I whispered.

Papa took my hand and quickly pulled me along. “Don’t look,” he whispered. “Learn not to see anything, or to be seen.”

I did learn, better than he could have imagined. There were ways to move about the streets so as not to draw attention to oneself. Those who did it well got home safely each night. I perfected it.

Which was important, because I’d also learned that the Nazis held

us in particular contempt. They wanted the Poles to see that if we were given the work of animals, we would do the work of animals. They wanted the world to think that we were less than human.

At first, I thought it would be impossible for any civilized person to believe such absurdities, such ugliness. But that was only the beginning …

By November, all Jews were required to wear the yellow Star of David on an armband, which created an entirely new set of problems for us. Now that we were easily identified, we became easy marks for Poles or Germans who considered harassment a cheap form of entertainment.

One day, Mama took us into town. We were supposed to meet Papa at the corner outside his shoe repair shop, but then we heard a commotion nearby. Mama let out a small cry and tried to pull us away, but I recognized my father’s black fedora.

“No,” I growled as I broke free. “What are they doing?”

He had been stopped by a Polish police officer who was making him stand at attention while he ripped out pieces of my father’s beard, one fistful at a time. With every tear, my father grunted with pain, but he said nothing and offered no form of resistance. The crowd that had gathered pointed at him and laughed, as if humiliation and pain were some kind of joke. The closer I got, the angrier I became. How could they do such a thing? These were people who had been peaceful toward us in the past. Some had even been our friends.

I started forward, determined to defend my father, but Yitzchak grabbed me from behind and dragged me away from the crowd. “We have to help him!” I said, still fighting.

Mama was by my side then and spoke firmly. “Don’t make it worse, Chaya. Let it be.”

By then, the officer had finished with my father, and he was waving the crowd away. At one time, this would have been shocking behavior, but gradually such abuse became common. Now it was accepted. The officer saw me glaring at him and only smiled, receiving pats on his back from members of the crowd. If he knew what I’d been thinking, he’d have arrested me.

Late that night, I heard my father crying with my mother at his side. I’d never heard him cry before, and it crushed my heart. Afterward, he avoided going out on the streets, and if he had to, then he walked with his eyes down, hands stuffed in his pockets. They had not just taken pieces of his beard. They had robbed my father of his dignity, which was far worse.

A Night Divided

A Night Divided Elliot and the Goblin War

Elliot and the Goblin War Elliot and the Last Underworld War

Elliot and the Last Underworld War Mark of the Thief

Mark of the Thief Rise of the Wolf

Rise of the Wolf Elliot and the Pixie Plot

Elliot and the Pixie Plot The Shadow Throne

The Shadow Throne The False Prince

The False Prince Wrath of the Storm

Wrath of the Storm Deadzone

Deadzone The Runaway King

The Runaway King The Warrior's Curse

The Warrior's Curse The Captive Kingdom

The Captive Kingdom The Scourge

The Scourge The Deceiver's Heart

The Deceiver's Heart Resistance

Resistance